10% of the author’s royalties for each book sold are donated to the Children of Armenia Fund (COAF).

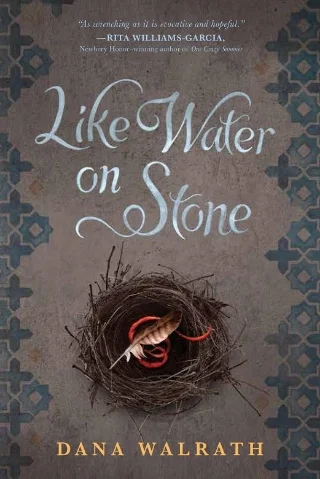

Like Water on Stone

It is 1914, and the Ottoman Empire is crumbling into violence. Beyond Anatolia, in the Armenian Highlands, Shahen Donabedian dreams of going to New York. Sosi, his twin sister, never wants to leave her home, especially now that she is in love. At first, only Papa, who counts Turks and Kurds among his closest friends, stands in Shahen's way. But when the Ottoman pashas set in motion their plans to eliminate all Armenians, neither twin has a choice. After a horrifying attack leaves them orphaned, they flee into the mountains, carrying their little sister, Mariam. But the children are not alone. An eagle watches over them as they run at night and hide each day, making their way across mountain ridges and rivers red with blood.

Awards

Notable Books for a Global Society Award Winner

Vermont Book Award Finalist

Bank Street College of Education Best Book of the Year with Outstanding Merit

YALSA Best Fiction Nomination

CBC Notable Social Studies Trade Book of the Year

Blurbs

“I have walked through the remnants of the Armenian civilization in Palu and Chunkush, I have stood on the banks of the Euphrates. And still I was unprepared for how deeply moved I would be by Dana Walrath’s poignant, unflinching evocation of the Armenian Genocide. Her beautiful poetry and deft storytelling stayed with me long after I had finished this powerful novel in verse.” —Chris Bohjalian, author of The Sandcastle Girls and Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands

"A heartbreaking tale of familial love, blind trust, and the crushing of innocence. A fine and haunting work." - Karen Hesse, Newbery Medal - winning author of Out of the Dust

"Like Water on Stone is as wrenching as it is evocative and hopeful. Dana Walrath has only begun to scratch the surface of her imaginative gifts."" - Rita Williams-Garcia, Newbery Honor Award-winning author of One Crazy Summer

"This eloquent verse novel brings one of history's great tragedies to life." - Margarita Engle, Newbery Honor - winning author of The Surrender Tree

“This novel in verse will grip your heart and coax you into one of humanity's darkest corners. Like Water on Stone is a work of great historical and literary significance." - Aline Ohanesian, author of Orhan's Inheritance

“This moving book shows that suffering can bring strength, courage, forgiveness, and hope for better humanity." - Yair Auron, author of The Banality of Denial

"Dana Walrath transports us to a lost world, the Armenian highlands in the late Ottoman Empire, and tells us the tragic and triumphant story of how some destined to die at the hands of their own government survived. Through images and words magical and evocative, she finds a way to convey what has elsewhere been said to be indescribableThis book reveals and heals at one and the same time." - Ronald Grigor Suny, William H. Sewell, Jr. Distinguished University Professor of History, The University of Michigan

Reviews

"A shocking tale of a bleak moment in history, told with stunning beauty." - Publishers Weekly, Starred

"This beautiful, yet at times brutally vivid, historical verse novel will bring this horrifying, tragic period to life for astute, mature readers." - School Library Journal, Starred

“Emotional and brutal, Like Water On Stone is the perfect book to pick up for the historical fiction fan.” - Bustle

“This is an excellent novel, highly recommended for any library.” - VOYA

“A powerful tale balancing the graphic reality of genocide with a shining spirit of hope and bravery in young refugees coming to terms with their world.” - Booklist

“A clear-eyed view of war and it’s brutal consequences.” - BookPage

“An unforgettable verse novel.” - TimesUnion.com

“Like Water on Stone blends haunting magical realism and free verse poetry to create a heartbreaking story that will haunt readers long after they have read the last page.” - Absolute Magazine

“Walrath contributes with her own eloquence to keeping the past alive-as both elegy and warning to the present.” - Seven Days

The Story Behind The Story

This story began, as many stories do, with a conversation. A sentence from that long-ago conversation has haunted me since I was a little girl. I asked my mother about her mother’s childhood in western Armenia. She replied, “After her parents were killed, she hid during the day and ran at night with Uncle Benny and Aunt Alice from their home in Palu to the orphanage in Aleppo.”

My grandmother Oghidar Troshagirian died long before I was born. My grandfather Yeghishe Mashoian, also a genocide survivor, died when I was six. Uncle Benny and Aunt Alice were colorful characters in my childhood, but I knew little about their lives. In my family, we didn’t speak about the genocide. My mother married an American, so my brother, my sister, and I grew up speaking English. By the time I thought to ask the serious questions, that generation was gone.

Long before I ever imagined that I might write this story, I filled in the gaps of my family history by reading everything I could about the Armenian genocide: accounts by eyewitnesses, such as Henry Morgenthau, the United States ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1916; oral histories; memoirs; academic tomes; and works of historical fiction. Still, I wanted more.

In the summer of 1984, my husband and I traveled to Palu. An unmarked Armenian church perched on the top of the hill above the town, its roof missing and its walls defaced. In town, vendors peddled ayran, the cool yogurt drink Armenians call tan. We asked if there were any mills nearby and were sent across a modern bridge, built next to one of crumbling stone with eight arches. We followed the river’s bank to a fast-flowing stream, then headed up the stream into the woods until we reached a mill with a series of attached buildings running up the slope.

On the rooftop of the largest building, the head-scarfed lady of the house served us sweet tea in clear glass cups. A half-dozen children with big brown eyes watched and listened. Mounds of apricots dried in the sun. She said that the mill had been in her family for sixty years; before that, it had belonged to Armenians. Anti-Armenian stories were running in Turkish newspapers that summer, and all visible traces of Armenian inhabitants had been systematically denied or destroyed, so I had kept my identity hidden as we traveled. But I told her the truth. We held each other’s gaze as the water hit the mill wheel and the stones of the stream. The official Turkish policy of genocide denial evaporated for one brief moment on that rooftop.